Novel approach to self-assembling mobile micromachines

- 25 June 2019

- Physical Intelligence

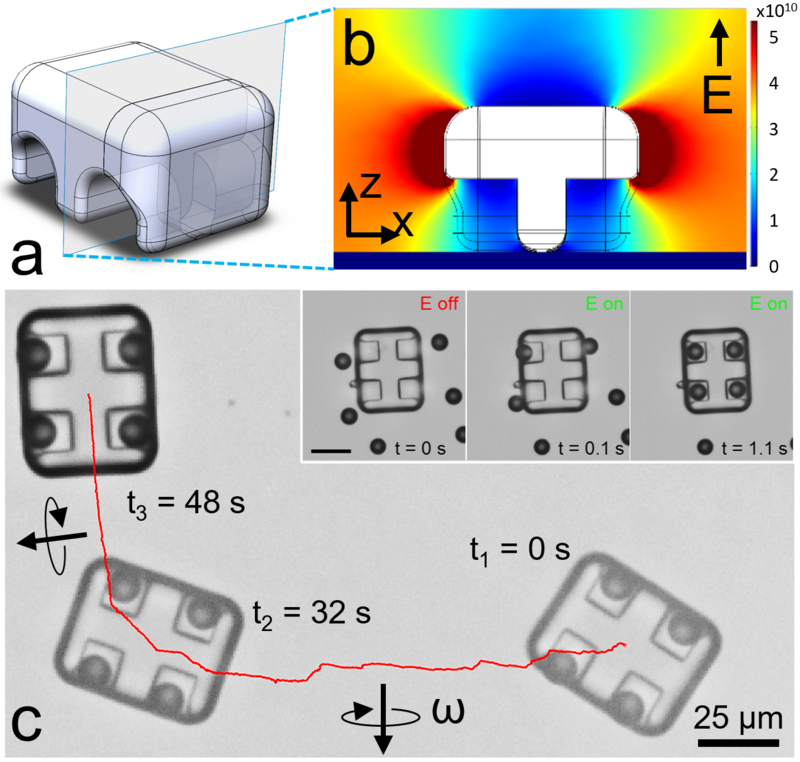

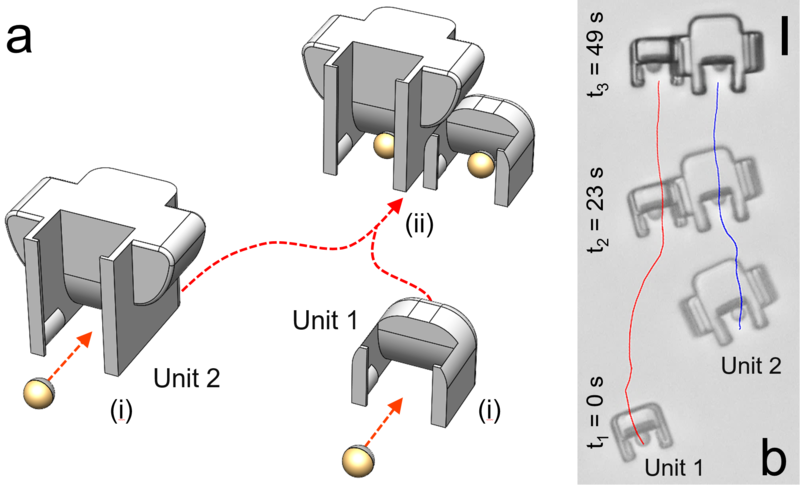

How the components come together depends on their design and shape and the resulting dielectrophoretic forces when exposed to an electric field.

Stuttgart – Building a robot with many different components is a challenging task. Even more so, if done at the micro scale. Self-assembly of particles is nothing new. In fact, it has been achieved for decades. Magnetic particles interacting under rotating magnetic fields self-assemble as do components bound together through chemical reactions. Bacterial microswimmers are one such example. However, the end result of these self-assembled micromachines has been very limited – until now.

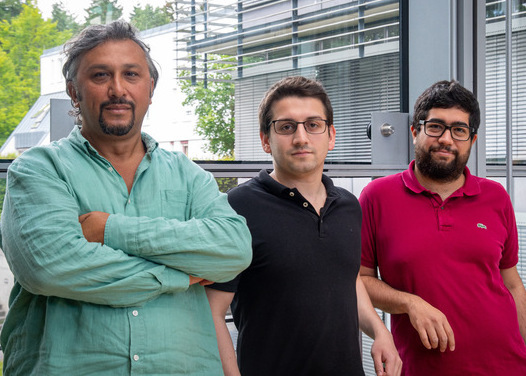

Scientists researching at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart (MPI-IS) took a new approach in self-assembling not one but many different shaped machines only 40 to 50 micro meters in size – about half the diameter of a human hair. They proofed that programmable self-assembly of their micromachines is possible solely through the design and structure of the individual components: by making use of dielectrophoretic forces that evolve around the individual parts when exposed to an electric field. In this environment, the design and structure of the machine frames on the one hand and magnetic actuators on the other allow their controlled configuration, making the assembly programmable. The scientists’ ground-breaking research was published in Nature Materials on 24th June 2019 with the title Shape-encoded dynamic assembly of mobile micromachines. Berk Yigit, a Ph.D. student in the Physical Intelligence Department at the MPI-IS, and Yunus Alapan, a Postdoc and Mechanical Engineer working in the same department, are both the lead authors of the above publication. Metin Sitti, Director at the MPI-IS and head of the Physical Intelligence Department is the last author.

“We take advantage of the shape- and material-specific forces in a non-uniform electric field,” Alapan explains. “The shape of the machine frame on the one hand and actuators on the other dictates the surrounding gradients. These cause a pulling-force between the units assembling the micromachine. By changing the shape, we control how these gradients are generated and hence how the components are attracted to one another.”

“The components of our micromachines can move relative to each other, which gives another level of complex locomotion,” Yigit says. “Imagine the wheels of a car rotating but the chassis stays unchanged: the car in its entirety moves forward and can go in many directions. Instead of forming rigid connections, each part can move individually.”

Building the individual components was done through a special 3D printing method using two-photon lithography. “Our first design was a microcar, as a homage to the ubiquity of wheeled propulsion in our lives”, Alapan continues. “We fabricated the 3D frame or chassis with its wheel-pockets as this structure generates very attractive gradient forces for the magnetic microactuators – the wheels. Within seconds of applying the electric field, the wheels self-assembled into these pockets!” The researchers then steered the microcar by a vertically rotating magnetic field as can be seen here.

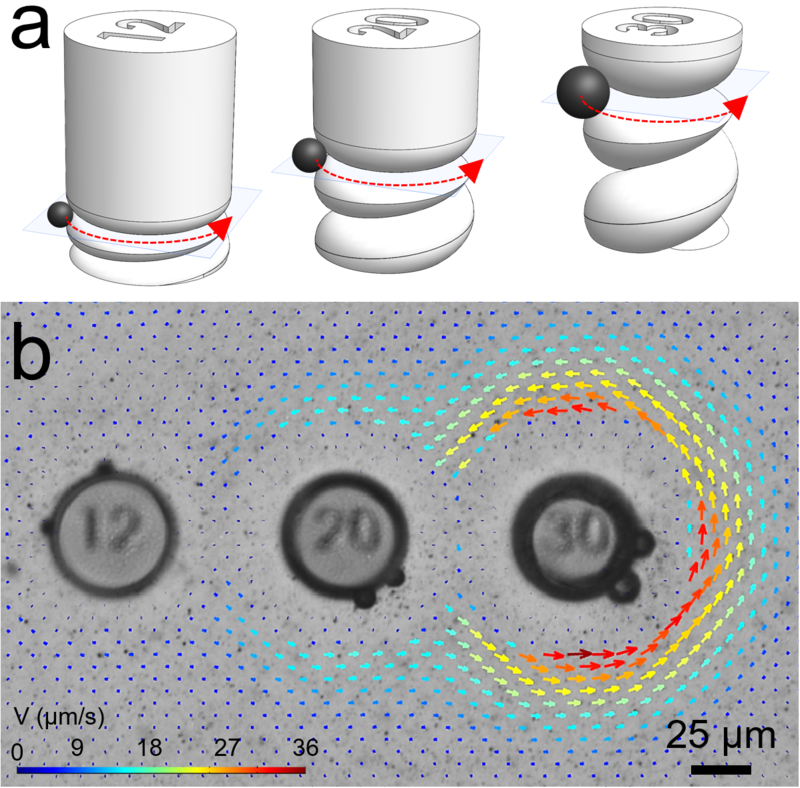

Alapan and Yigit tried out many different component sizes and shapes, their tiny self-assembled robots come in many varieties: The researchers were able to build a microcar, a microrotor, something that resembles a small rocket and even a micropump. While it is rotating, magnetic particles at the pumps’ periphery are being moved upwards along its spiral. This causes a pumping effect when one micropump is close to another. The researchers further showed that they can not only assemble motor and structural parts in a configurable way, forming microrobots, but also assemble several microrobots together paving the way for hierarchical multi-robot assemblies.

Being able to move in many different ways is of huge benefit: It could be the deciding factor whether or not such micromachines could one day be deployed in delivering drugs or sense tumor cells inside the body, where a versatile locomotion is key.

The above method of self-assembly to be able to build micromachines of many different shapes and sizes will have a great impact on the scientific community. “Mobile sensing, in vitro targeted drug delivery, single cell manipulation, and precise actuation at this scale are all a great challenge. This new approach could reduce the complexity of these tasks”, says Metin Sitti.

Video

About us

At the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems we aim to understand the principles of Perception, Action and Learning in Intelligent Systems.

The Max-Planck-Institute for Intelligent Systems is located in two cities: Stuttgart and Tübingen. Research at the Stuttgart site of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems covers small-scale robotics, self-organization, haptic perception, bio-inspired systems, medical robotics, and physical intelligence. The Tübingen site of the institute concentrates on machine learning, computer vision, robotics, control, and the theory of intelligence.

The MPI-IS is one of the 84 Max Planck Institutes that are part of the Max Planck Society. It is Germany's most successful research organization. Since its establishment in 1948, no fewer than 18 Nobel laureates have emerged from the ranks of its scientists, putting it on a par with the best and most prestigious research institutions worldwide. All Institutes conduct basic research in the service of the general public in the natural sciences, life sciences, social sciences, and the humanities. Max Planck Institutes focus on research fields that are particularly innovative, or that are especially demanding in terms of funding or time requirements. And their research spectrum is continually evolving: new institutes are established to find answers to seminal, forward-looking scientific questions, while others are closed when, for example, their research field has been widely established at universities. This continuous renewal preserves the scope the Max Planck Society needs to react quickly to pioneering scientific developments.

Dr. Metin Sitti is the Director of the Physical Intelligence Department at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems, based in Stuttgart.

Sitti received his BSc and MSc degrees in electrical and electronics engineering from Bogazici University in Istanbul in 1992 and 1994, respectively, and his PhD degree in electrical engineering from the University of Tokyo in 1999. He was a research scientist at University of California at Berkeley during 1999-2002. During 2002-2016, he was a Professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, USA. Since 2014, he is a Director at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems.

Sitti and his team aim to understand the principles of design, locomotion, perception, learning, and control of small-scale mobile robots made of smart and soft materials. Intelligence of such robots mainly come from their physical design, material, adaptation, and self-organization more than to their computational intelligence. Such physical intelligence methods are essential for small-scale milli- and micro-robots especially due to their inherently limited on-board computation, actuation, powering, perception, and control capabilities. Sitti envisions his novel small-scale robotic systems to be applied in healthcare, bioengineering, manufacturing, or environmental monitoring to name a few.

Dr. Yunus Alapan is a post-doctoral scientist and Humboldt Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Physical Intelligence Department of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart. Dr. Alapan received his BSc and MSc degrees in mechanical engineering from Yildiz Technical University in Istanbul in 2011 and 2012, respectively, and his PhD degree in Mechanical Engineering from the Case Western Reserve University in 2016. Dr. Alapan works at the interface of robotics, biology, and soft matter, developing biomimetic and soft micro-robots/systems inspired by nature.

Dr. Alapan won first place in NASA Tech Briefs’ Create the Future Design Contest in the Medical Category in 2014 and Student Technology Prize for Primary Healthcare organized by the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology in 2016. His postdoctoral work is being funded by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation since February 2017.

Berk Yigit is a Ph.D. student in the Physical Intelligence Department of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart. Yigit received his BSc degree in 2012 from the Mechanical Engineering Department, Bogazici University and his MSc degree in 2014 from the Biomedical Engineering Department, Koc University. Yigit is also a Ph.D. student in Mechanical Engineering at Carnegie Mellon University based in Pittsburgh since 2014. Yigit develops self-organizing robotic matter that form microscopic swarms and machines inspired by living systems in his Ph.D. work.